By John Payne

Overview

This blog is a narrative description of my efforts to develop an AI pipeline to recognize wildlife, livestock and other objects from aerial photos taken during surveys of large mammals from light aircraft. The work is my contribution to a project run by Howard Frederick, from the Tanzanian Wildlife Research Institute. I initially thought it would be straightforward, but the real world contains all sorts of tradeoffs and it has been interesting and challenging to get as far as we have. I hope that readers may find some relief and humor from my story because they struggled with things that I did (or can’t believe how dumb I was), and may perhaps even find a snippet or two that is useful to them.

The code referred to is available in the aerial_survey_ai Github repository.

This project has been generously supported by Microsoft’s AIForEarth program (AI4E), which provided us with credits on Microsoft’s Azure cloud computing ecosystem, as well as good advice, technical support, and the opportunity to meet other grantees. I am very grateful for their support.

Introduction to the problem

For decades, the standard way to do an aerial wildlife survey was to fly some sort of grid pattern and have human observers in an airplane count and photograph things that they saw. However, humans are expensive, they get tired, and they miss animals. With the advent of digital photography and drones, it is becoming easier to fly transects and take nearly continuous photographs. A moderate-sized survey can easily generate 100,000 images. The challenge then becomes figuring out how to detect objects in those images. In most wildlife surveys, at least 95% of the images are ‘empty,’ meaning they contain no objects of interest. Proof-of-concept work has shown that wildlife counts obtained by manually counting animals in photographs after a survey flight are at least as accurate as counts done by human observers during a survey flight, but the time required to detect animals in large collections of photographs has limited the applicability of the photographic method, so far.

In 2013, I joined a survey of wildlife and livestock of over 150,000 km² of the Mongolian Gobi Desert, with Howard and two of his colleagues: Mike Norton-Griffiths (the project leader and author of the classic aerial survey textbook, Counting Animals) and Dana Munro Slaymaker, a digital survey and FLIR expert. The survey generated more than 100,000 photographs, and it took a team of 6 people two months working full-time to go through them. The photographic analysis required a complicated lab setup with identical workstations and a back-end database to feed the annotators batches of images, track the progress of image annotation, compare annotators against each other, estimate false-positive and false-negative error rates by double-counting a fraction of the images, and so on. It was an expensive and complicated proposition. Although it will probably always be necessary to have humans in the loop, that experience helped to solidify our determination to reduce the amount of human work that is necessary by developing a machine learning pipeline for object detection in aerial images.

Conservation arguments over elephant numbers prompted Paul Allen’s Vulcan Inc. to fund the Great Elephant Census in 2016, which was a first attempt to do nearly simultaneous surveys of elephants across subSaharan Africa. Howard was one of the technical leads for the project. The census was successful, but the extreme difficulty of pulling it off highlighted the need for better methods. If surveys are to be used for monitoring wildlife (or anything else) it is important for them to be done regularly and often, and for the results to be available quickly.

Our goal is to make aerial surveys easier to do, cheaper to analyze, and ultimately more accurate. In particular, we would like to make them more accessible to government wildlife and agricultural departments in developing countries. We are working on aspects of that challenge; to be specific, Howard is designing inexpensive camera systems and associated equipment, doing ongoing surveys and training in southern and eastern Africa, and leading collaborations with a variety of people and organizations on many aspects of surveys, while I have been beavering away at using AI for object detection. Together, we are designing a workflow that takes data from the airplane on a dusty runway to the local wildlife department, to the cloud, through an AI pipeline, and back out in the form of numbers that can be analyzed statistically.

Understanding aerial surveys

Survey workflow

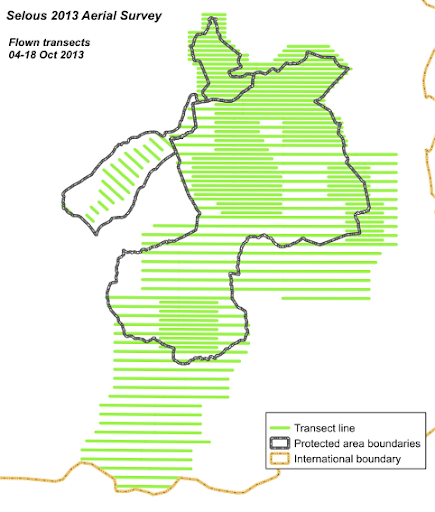

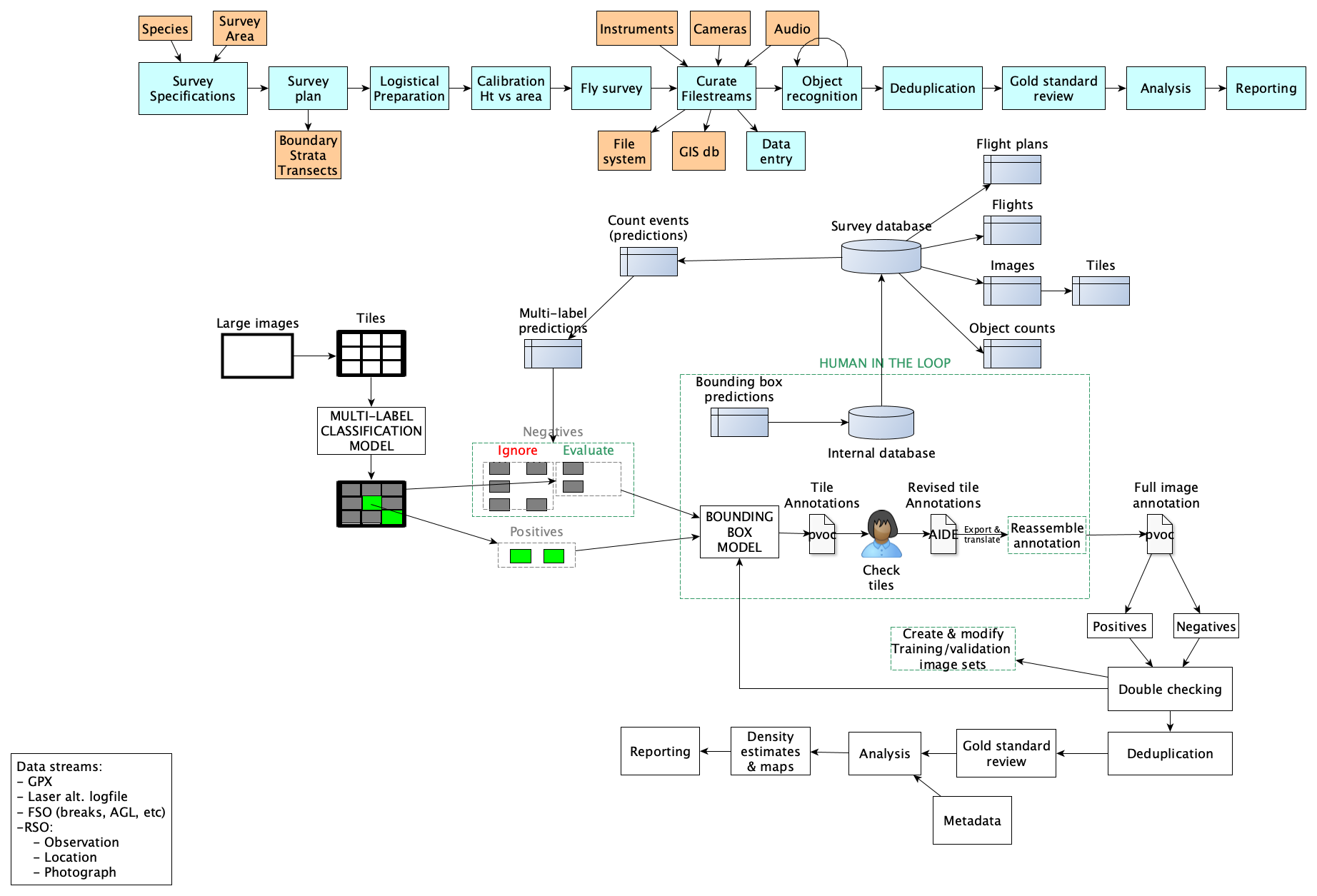

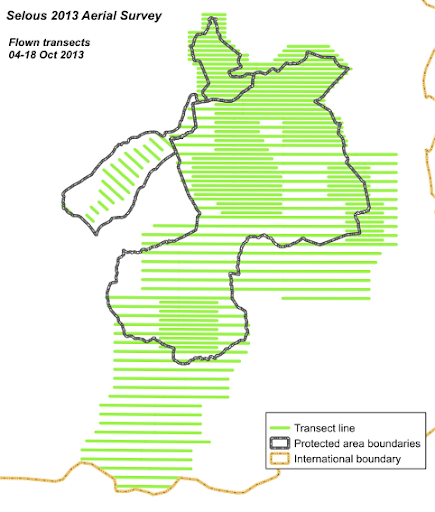

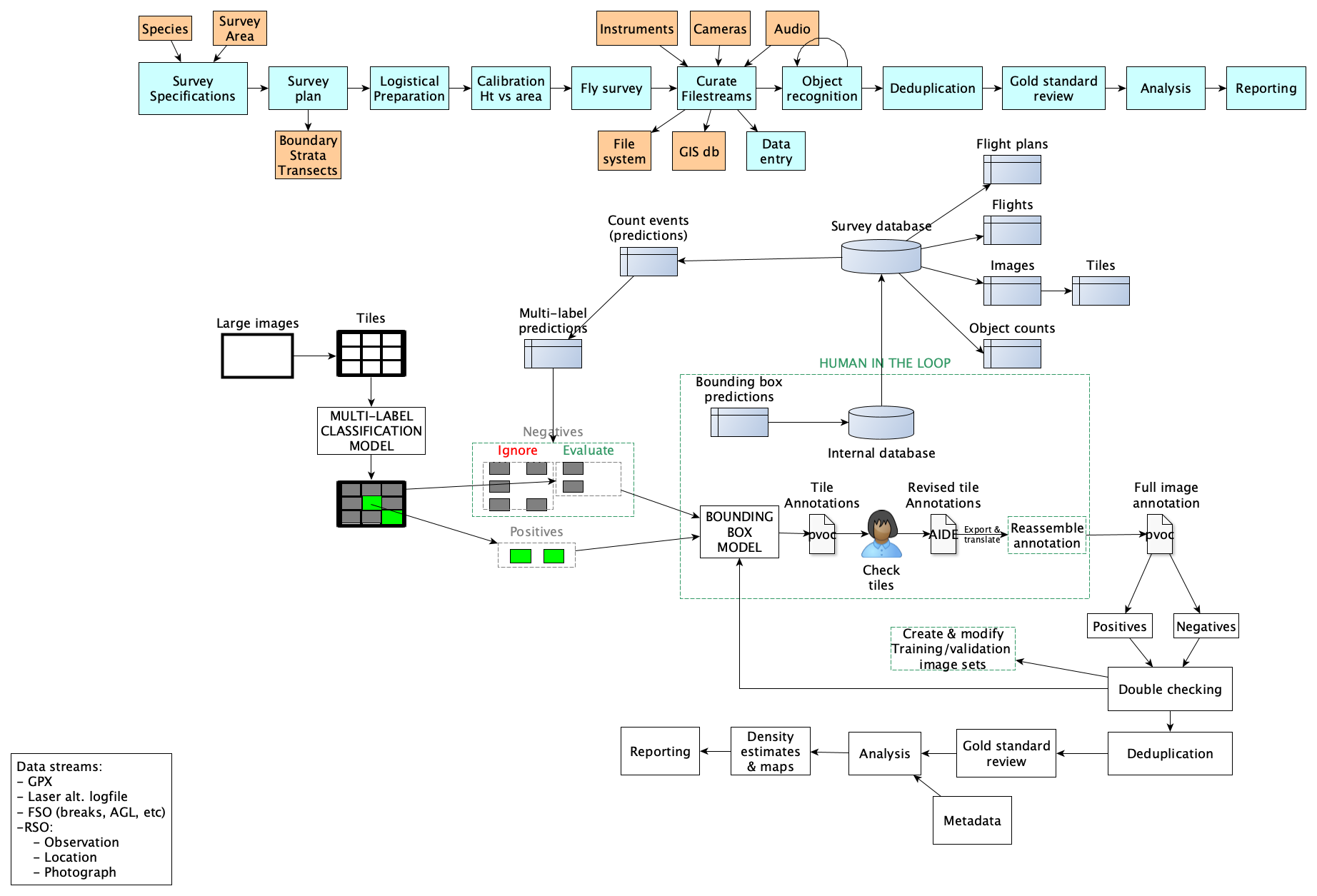

An aerial survey is a complicated beast. The goal is usually to obtain counts or density estimates, or possibly to measure indicators, for some objects of interest over a large area. Howard and I drew this diagram together the other day, trying to picture all of the components. The top band shows the overall survey workflow. The rest of the diagram shows roughly what is needed for just the object recognition box, which is only a small part of the total workflow.

AI priorities are different for an aerial survey!

The aim of an aerial wildlife or livestock survey is to estimate the numbers and spatial distribution of animals that are usually very rare (sometimes present in < 1% of all images), clumped together, and often half-hidden in forest or water environments. Many of the more successful examples of computer vision - such as recognition of camera trap photos - have much larger targets relative to the whole image, and consistent backgrounds; aerial images have far smaller objects of interest in a wider field, over widely varying habitats.

The precision and accuracy of the density estimates ultimately depend on a number of different sources of error, but one of the top sources of error is that surveys sample only a small fraction of the entire landscape. Any error made in counting animals in the sampled areas will balloon when it is extrapolated to the whole landscape.

Therefore, the priorities of AI for a survey are different than the priorities of AI in other applications. The priorities in descending order of importance are:

- Never fail to detect an animal that is present in an image. In practice, surveys require a very low false-negative rate above all else because the precision of a survey, which affects its ultimate usefulness in monitoring, is tied to the false-negative rate. Furthermore, quantifying the residual false-negative rate is very important in the final analysis, and this requires re-counting a proportion of the “negative” images.

- A relatively low false-positive rate. If there are too many false-positives, then the model doesn’t save the human annotators much work. Ideally, the false-positive rate should be well below 5%.

- Reasonable speed. Surveys generate a lot of images, and a model isn’t very useful if it doesn’t run fast enough. Speed is especially critical if large images must be cut into tiles, which multiplies their numbers.

- Perhaps surprisingly, Accurate species identification is a relatively low priority. In most cases, there are few enough animals that humans will be scrutinizing every photograph that contains animals. The role of the model is primarily to sort through vast piles of empty images to find animals in the first place. In practice, AI models get really good at species identification anyway, and we don’t mind if rare species are occasionally misidentified.

- Accurate instance counts. For some surveys (for example, counting nesting birds on a colony), accurate instance counts may be a high priority. But for our uses, correct instance counts are a relatively low priority because people will be examining most or all of the photographs that contain animals. Counting is always made difficult by the fact that animals often stand close together (particularly mothers and offspring) or pile on top of each other. In our case, the tiling process described below makes counting more difficult because it’s hard to ensure that there is no duplication between object instances.