I was getting excited that we were ready to do inference and to finally deploy the model. I took a deep dive into Azure DevOps, Kubernetes clusters and web endpoints, and got as far as running the model in a container (which required ‘registering’ the model, among other steps). I was discouraged to find that it ran far too slowly, and upgrading the container with a GPU proved too difficult and expensive. So I abandoned that approach and decided to stick with working on VMs for now.

But I had nagging doubts. How slow was the model, I wondered? And had I done something wrong? I had a series of exchanges with Yu Wuxin, the Detectron2 wizard at Facebook, in which I built a reproducible example, tested it on various Azure and Google machines, and finally concluded that it took 0.2 seconds per 800x800 image; a result that he eventually agreed was probably correct.

It was really dismaying to realize that if we started with 100,000 images from a survey, multiplied that by 54 tiles/image * 0.2 seconds/tile on an Azure NC_v3 machine that cost $13.50/hour, then we were looking at a cost between $1000 and $10,000 (depending on how many problems we could solve) to run the tiles through the model once. That was clearly unsustainable (at least, in our impoverished field, and certainly for most wildlife departments in developing countries). Something had to give!

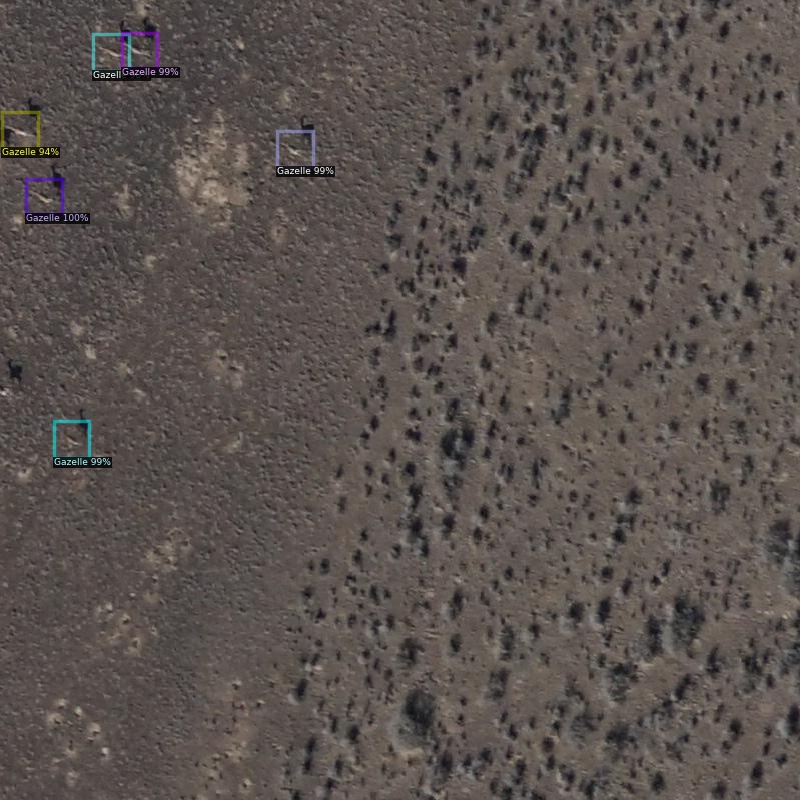

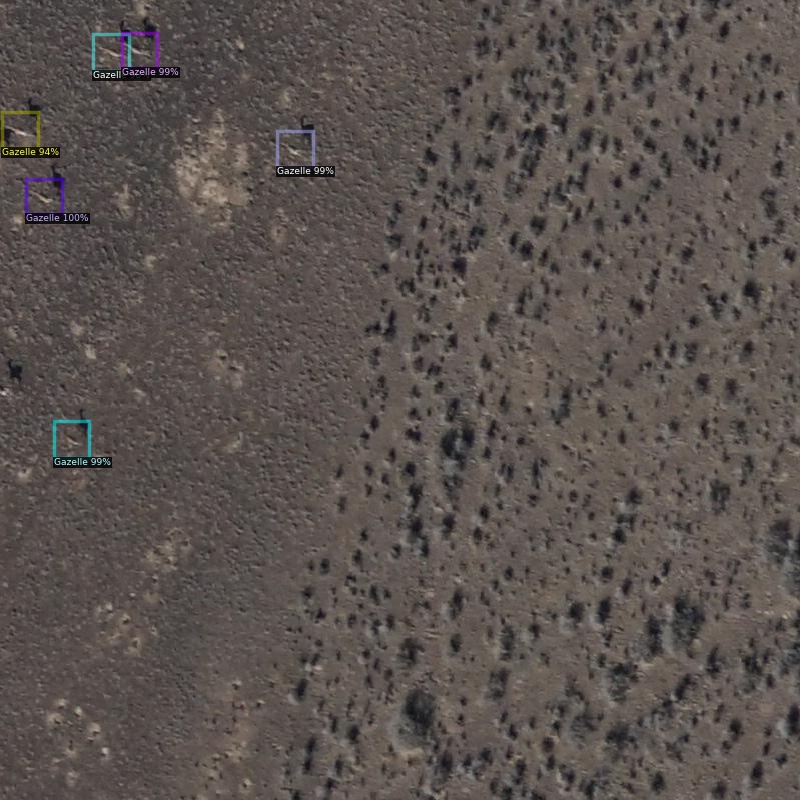

At this point, I took a break from inference problems and created a new model for a colleague of mine, Petra Kaczensky, who was doing drone surveys of wildlife in Kazakhstan. I followed most of the same steps as before (except I was smarter about being hyper-organized from the outset so there were fewer problems assembling training data), and used transfer learning to train a new head for the Tanzania Detectron model. Kazakhstan was an interesting challenge because the environment is much drier and wildlife is so scarce that very few images of the key species were available, so the training set was very small. We augmented pictures from Kazakhstan with some from Mongolia, which has some of the same species and a similar desert environment, and with some wildlife images from Tanzania. Despite the challenges, we fairly soon had decent results on the TridentNet model (OK that’s an exaggeration, it was actually a lot of work).

The inference speed roadblock remained, however, and it posed the same challenges in Kazakhstan as it did in Tanzania.

These gazelles were hard to see but the model found them.

A lovely group of khulan (wild asses). Note how the model has learned the animals, and not their shadows.