I learned the hard way that the most difficult part of an AI project is assembling the training and validation datasets. Why? Because you will almost certainly be assembling images and annotations from a variety of sources in order to get a large enough sample size, a good balance between categories, and as large a diversity as possible of images– including backgrounds, lighting, perspectives, and so on. The images and annotations must match, or at a minimum, it has to be clear which images have been checked. You will be astounded at how many things can go wrong; it is truly the Land of Edge Cases – there was even one time where the images I received had been tiled to a different size, so I had to merge the input tiles back into full-size images before re-tiling them. In short, I failed to insist on a high level of organization right off the bat, and I paid for it. I make some recommendations for how to do it better in the 03_process_annotations.ipynb notebook.

Getting the TridentNet model to run was slow because Detectron2 has a variety of different implementations including bounding-box models, instance segmentation, keypoints, and so on, documentation is quite limited, and not that many people seem to use it (or perhaps they all knew what they’re doing, unlike me). Detectron2 has its own environment that includes ‘registered’ datasets, custom data loaders, multi-GPU management, internal logging, and so on. The default training cycle was a bit clunkier than I wanted, and I realized early on that I’d need additional image augmentation, given that my sample size was relatively small. It took time to figure out how to get Detectron2 training efficiently on multiple GPUs, and I added some other customizations, including fixing a routine that helped to balance the sample size across categories, bypassing an evaluation routine, passing in-memory tiles to a custom dataloader, adding an Adabound optimizer, and others. Model customizations are in trident_project/dev_packages/trident_dev/model.py).

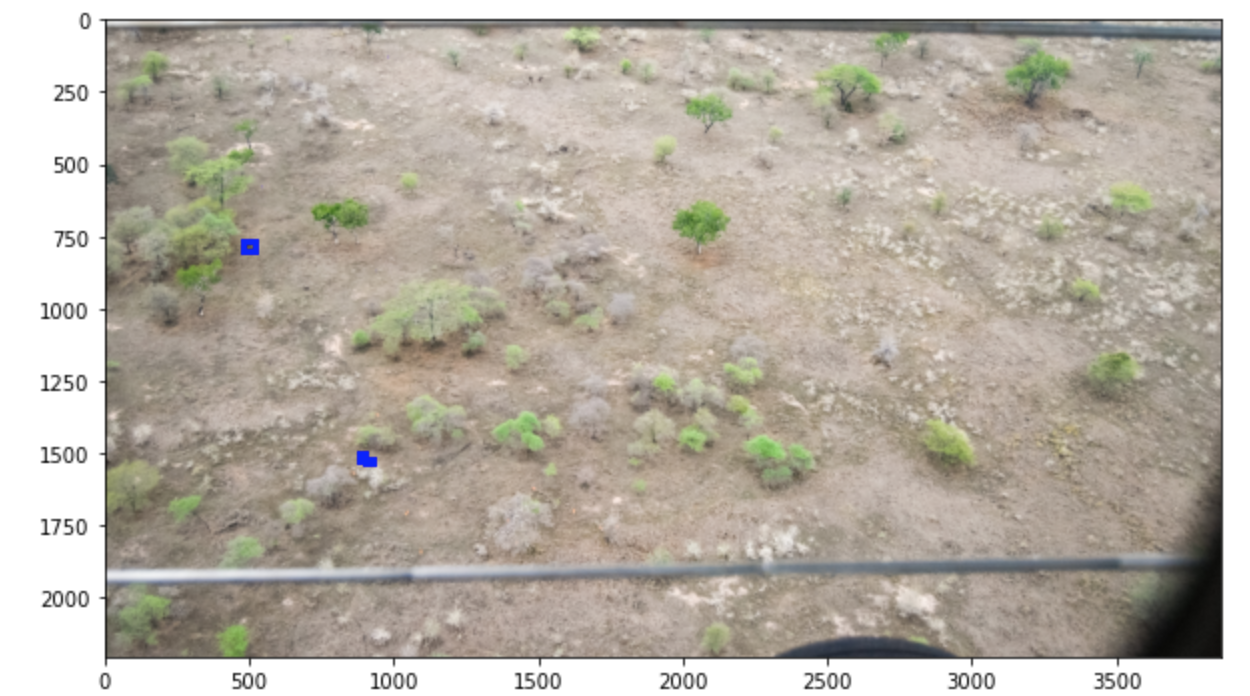

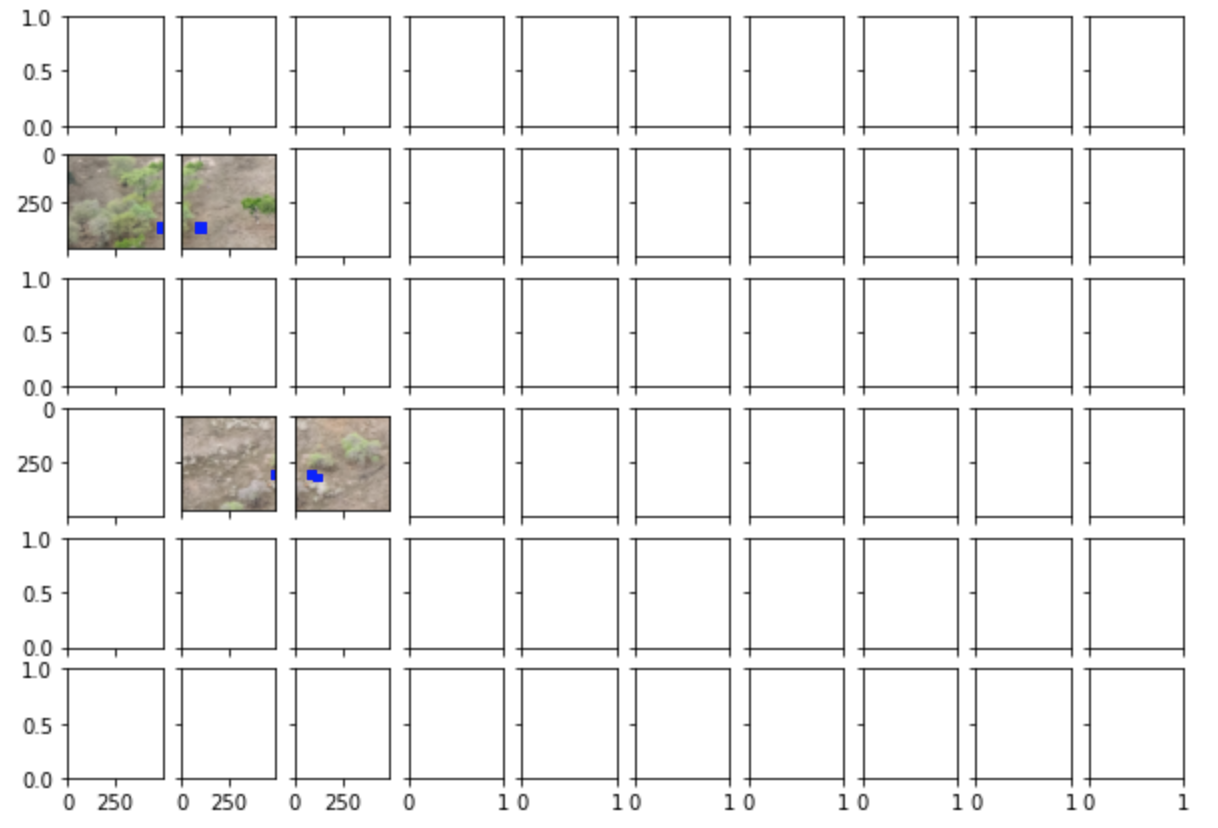

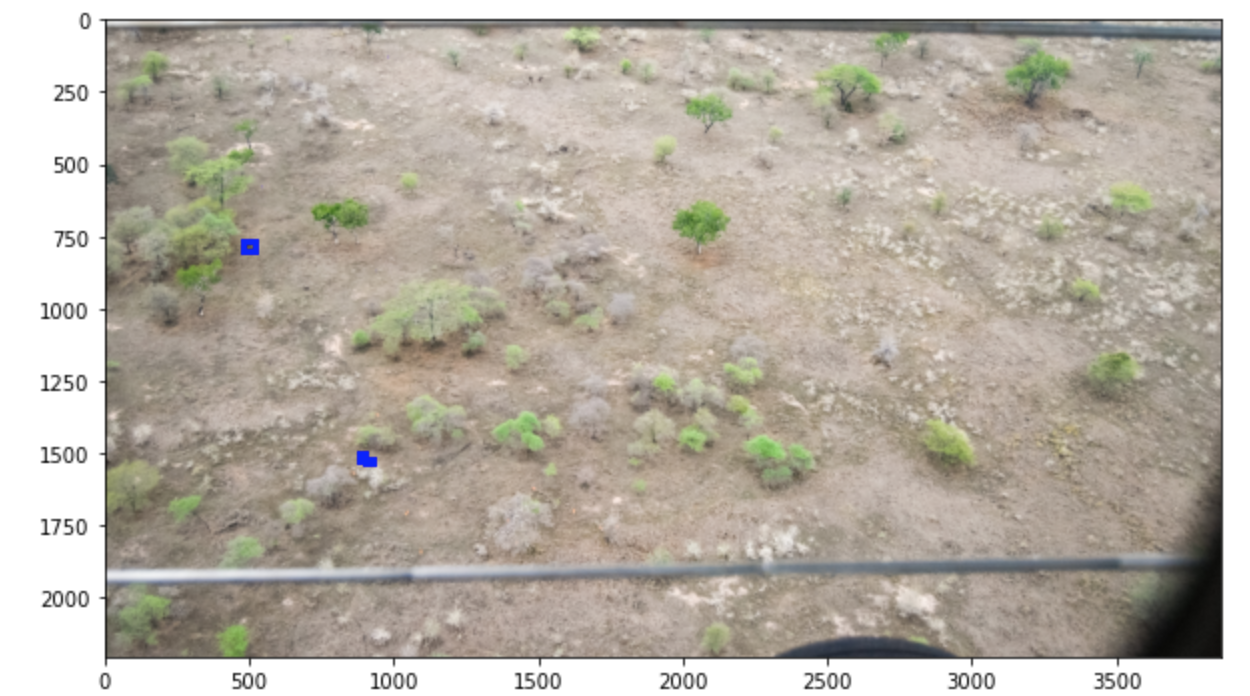

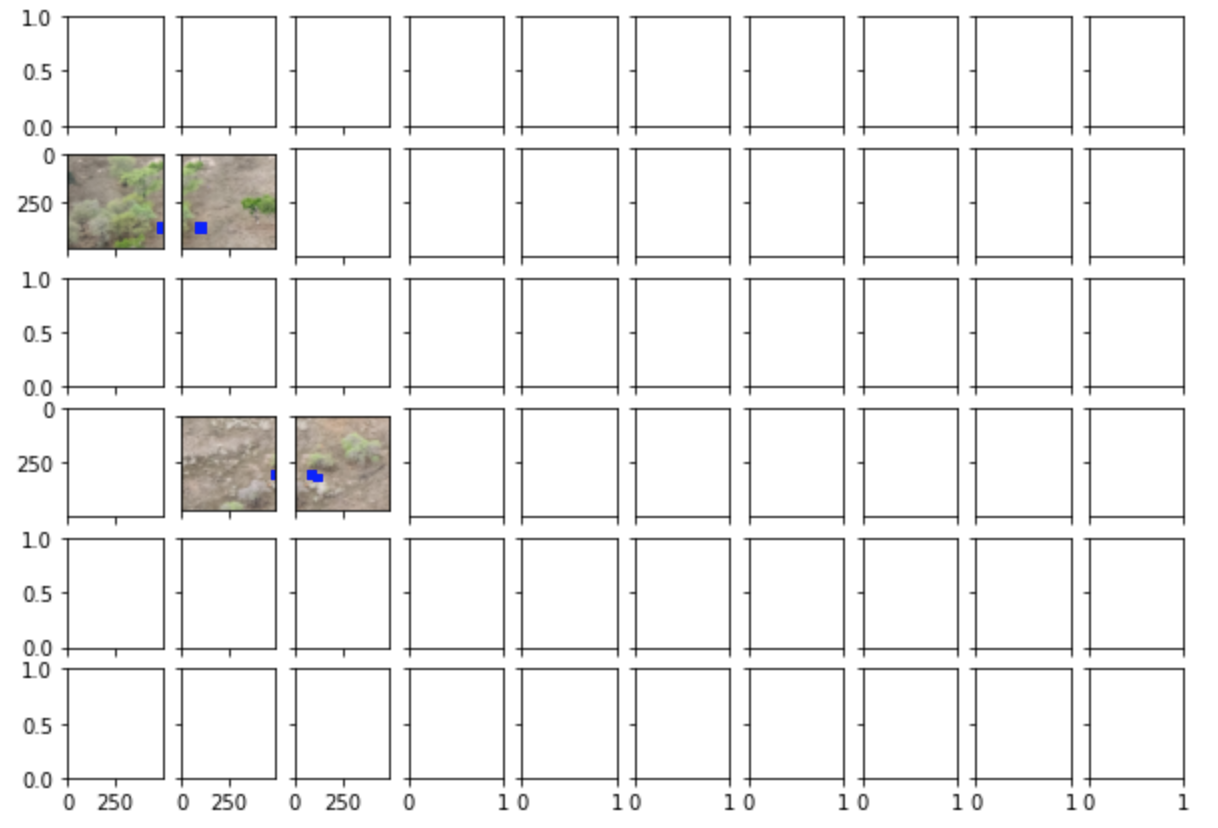

The current generation of GPUs can’t handle full-sized images from modern cameras, so the first step in preparing an image for an AI model is almost always to resize it, making it much smaller and sacrificing a lot of resolution. If the object of interest fills a large proportion of the image area, then that approach works perfectly well. But in an aerial survey of livestock or wildlife, a small object like a goat or gazelle might only occupy 30 pixels in an image that could contain tens of millions of pixels. That means we can’t afford to resize the image and lose resolution. The standard solution is to chop it into pieces, or ‘tiles’.

I still haven’t found good workflows for tiling, but I found a package that did some of what I wanted and forked it (my version is still rough; it’s trident_project/dev_packages/image_bbox_tiler.py).

In the process of building a training set of tiles from a set of full-size images and annotations, I uncovered a problem I hadn’t anticipated, which was that when you chop a bounding box into pieces, you may end up with little fragments that you don’t necessarily want to keep. I figured out a set of rules for deciding which to drop. Those are described in the 04_tile_training_images.ipynb notebook.

I also revised the tilling package to omit most of the empty tiles, but to randomly sample a small percentage of them. Having a good selection of empty tiles is important to training a model when 95% of the tiles that the model will see during inference are expected to be empty.

Writing tiles to disk is a very slow and resource-intensive process, so I decided to try holding the tiles in memory and passing them directly to the model. That turned out to be quite complicated because AI modeling code always expects to have the same number of annotations and images. In brief, I ended up creating a new dataloader for the tiles from each full-size image. It works well for a single GPU and for distributed training, but I still don’t have it set up quite right for distributed inference because Detectron2 spawns processes deep in the codebase in a way that I haven’t been able to fully understand. I’ve managed to increase the inference speed by 2X with 4 GPUs, but it should be roughly 4X faster, so I’m still missing something.